In the pursuit of weight loss, we often focus on diet and exercise, but there’s a crucial factor that tends to be overlooked: sleep. The relationship between sleep and fat loss is not a simple one, but numerous studies reveal the significant impact that sleep, or the lack thereof, can have on our bodies.

In the pursuit of weight loss, we often focus on diet and exercise, but there’s a crucial factor that tends to be overlooked: sleep. The relationship between sleep and fat loss is not a simple one, but numerous studies reveal the significant impact that sleep, or the lack thereof, can have on our bodies.

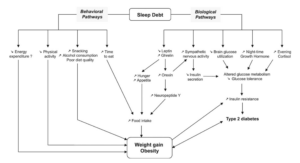

While it might not be straightforward to assert that more sleep directly leads to weight loss, the evidence overwhelmingly supports the notion that sleep restriction can be detrimental to BMI, obesity, and overall body weight. This impact is observed through various biological pathways that influence our eating behaviors.

Ghrelin and Caloric Consumption:

Our bodies naturally produce a “hunger hormone” called ghrelin. This hormone is secreted in the stomach, specifically the enteroendocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract. This hormone produces our drive to eat, as levels are highest before a meal, but drop down after eating.

Studies, such as the one conducted by Chapman et al. in 2013, demonstrated that sleep-deprived individuals experienced higher ghrelin concentrations, leading to increased calorie and food intake. Another study involving lean men showed a 22% increase in energy intake and a 98% spike in fat consumption after just two nights of insufficient sleep (Brondel et al., 2010). These findings suggest a direct link between sleep deprivation and altered eating behaviors, potentially contributing to fat accumulation.

Hormonal Imbalance:

Sleep deprivation disturbs the balance of various hormones involved in metabolism and energy balance. Leptin, known for inhibiting appetite, decreases, while ghrelin, an appetite stimulant, increases. This hormonal imbalance, combined with elevated cortisol levels and reduced brain glucose utilization, creates an environment conducive to weight gain.

Associations with Obesity:

Numerous studies have established associations between sleep duration and obesity. Locard et al.’s pioneering study in 1992 revealed a significant risk factor for obesity in children: reduced sleep duration. Subsequent research, including a meta-analysis by Cappuccino et al. in 2008, linked adults reporting less than 5 hours of sleep to a higher risk of obesity. Additionally, Ford et al. (2014) found that short sleep duration was associated with central obesity, emphasizing the importance of both quantity and quality of sleep.

BMI and Hormonal Regulation:

Specifically examining BMI, research consistently shows that shorter sleep durations are linked to increased BMI. Individuals sleeping less than 8 hours often exhibit reduced leptin and elevated ghrelin levels, creating a hormonal environment conducive to increased appetite and, subsequently, higher BMI.

Historical Evidence:

Historical studies, such as Mullington et al. (2003) and Spiegel et al. (1999), reinforce the connection between sleep loss and hormonal imbalance. Prolonged sleep loss was shown to decrease the circadian amplitude of leptin, while sleep restriction was associated with a reduction in mean leptin levels and an increase in ghrelin levels.

While correlation does not always imply causation, the overwhelming body of evidence suggests that insufficient sleep contributes to weight gain and obesity. As we strive for fat loss, it’s crucial to recognize the importance of quality sleep in supporting overall health and well-being. Prioritizing adequate sleep may prove to be a powerful yet often underestimated strategy in the journey towards a healthier, leaner body.

References

Brondel, L., Romer, M. A., Nougues, P. M., Touyarou, P., & Davenne, D. (2010). Acute partial sleep deprivation increases food intake in healthy men. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(6), 1550–1559. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28523

Cappuccio, F. P., Taggart, F. M., Kandala, N.-B., Currie, A., Peile, E., Stranges, S., & Miller, M. A. (2008). Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep, 31(5), 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/31.5.619

Chapman, C. D., Nilsson, E. K., Nilsson, V. C., Cedernaes, J., Rångtell, F. H., Vogel, H., Dickson, S. L., Broman, J.-E., Hogenkamp, P. S., Schiöth, H. B., & Benedict, C. (2013). Acute sleep deprivation increases food purchasing in men: Sleep Deprivation and Food Purchase. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 21(12), E555-60. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20579

Fleck, S. J., & Kraemer, W. J. (2014). Designing resistance training programs. Fourth edition. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Ford, E. S., Li, C., Wheaton, A. G., Chapman, D. P., Perry, G. S., & Croft, J. B. (2014). Sleep duration and body mass index and waist circumference among U.S. adults. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 22(2), 598–607. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20558

Knowles, O. E., Drinkwater, E. J., Urwin, C. S., Lamon, S., & Aisbett, B. (2018). Inadequate sleep and muscle strength: Implications for resistance training. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 21(9), 959–968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2018.01.012

Locard, E., Mamelle, N., Billette, A., Miginiac, M., Munoz, F., & Rey, S. (1992). Risk factors of obesity in a five year old population. Parental versus environmental factors. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 16(10), 721–729. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1330951/

Mônico-Neto, M., Antunes, H. K. M., Dattilo, M., Medeiros, A., Souza, H. S., Lee, K. S., de Melo, C. M., Tufik, S., & de Mello, M. T. (2013). Resistance exercise: a non-pharmacological strategy to minimize or reverse sleep deprivation-induced muscle atrophy. Medical Hypotheses, 80(6), 701–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2013.02.013

Mullington, J. M., Chan, J. L., Van Dongen, H. P. A., Szuba, M. P., Samaras, J., Price, N. J., Meier-Ewert, H. K., Dinges, D. F., & Mantzoros, C. S. (2003). Sleep loss reduces diurnal rhythm amplitude of leptin in healthy men: Reduced diurnal rhythm amplitude of leptin. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 15(9), 851–854. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01069.x

Paoli, A., Gentil, P., Moro, T., Marcolin, G., & Bianco, A. (2017). Resistance training with single vs. Multi-joint exercises at equal total load volume: Effects on body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, and muscle strength. Frontiers in Physiology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.01105

Spiegel, K., Leproult, R., & Van Cauter, E. (1999). Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet, 354(9188), 1435–1439. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01376-8

Spiegel, Karine, Tasali, E., Penev, P., & Van Cauter, E. (2004). Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Annals of Internal Medicine, 141(11), 846–850. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00008

Taheri, S., Lin, L., Austin, D., Young, T., & Mignot, E. (2004). Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Medicine, 1(3), e62. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062

Thun, E., Bjorvatn, B., Flo, E., Harris, A., & Pallesen, S. (2015). Sleep, circadian rhythms, and athletic performance. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 23, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.11.003

Vitale, K. C., Owens, R., Hopkins, S. R., & Malhotra, A. (2019). Sleep hygiene for optimizing recovery in athletes: Review and recommendations. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(8), 535–543. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0905-3103

Leave a Comment